It's all in the genes

We hear about genes all the time, but do we really know what they are?

6/13/20243 min read

We've probably all heard someone say, "I must have the gene for X" where X is a characteristic that defines them. This notion suggests that each characteristic, either physical or a personality trait, is the result of the action of just one gene (when I say action I mean expression, but I'll explain that later). 20 years ago (before the first human genome was sequenced) some scientists might have thought along these lines too. Estimates of the number of genes in the human genome ran into the hundreds of thousands, but once the sequence was complete it quickly became clear that the answer was close to 20 thousand. This was a bit of a surprise, as humans have fewer genes than other 'lesser' animals. In fact even the tiny water flea has over 30 thousand. So how can it be possible that so few genes are required for the development of such a complex being as a human?

Well, first let's go back to the question of what a gene is. The central dogma of biology (as it's known) describes the flow of information within a biological system. More specifically it states that genetic information flows from DNA to RNA to protein. I haven't described RNA yet (and it appears in many forms) but you can think of it as a cousin of DNA with some very similar characteristics and some different. I could spend a lot more time talking about RNA but for the purposes of this post that is sufficient. Now, where was I?..

So we could describe a gene as a section of DNA or a piece of genetic information that includes the instructions to make a protein. But not all proteins are generated in all cell types. Each protein may have a small number of functions within the cell where it is produced, or it might have multiple functions in many different cell types. Furthermore, many proteins influence the function of other proteins (e.g changing the level of activity of a protein by binding to it or modifying it in some way) or affect the flow of information by binding to DNA and controlling how much of a protein is produced. This was a major focus of my PhD.

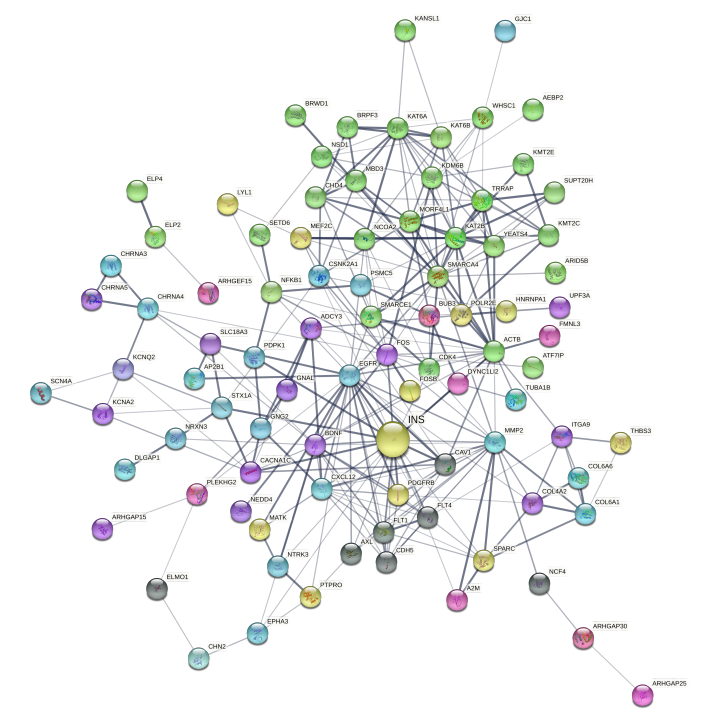

During my PhD I investigated various mechanisms controlling insulin levels in beta cells (cells that produce insulin) that had become cancerous. The image below is taken from my thesis and I've included it here simply to illustrate how complicated the picture can get.

So maybe you can start to see that the reality of how characteristics or traits are determined is often far more complicated than just the expression of one gene, and in many cases we still don't understand how it all works. That's even before we start discussing the effect of mutations in DNA (changes to the sequence of base pairs), which can change both the structure and function of the protein or effect how much of it is produced.

Finally, just in case I haven't confused you enough, the flow of information doesn't always make it to the protein level - some bits of DNA carry the instructions to make RNA that has a function unrelated to making a protein. This makes the definition of a gene a bit more blurry, and if you describe all these non-protein-making bits of DNA as genes then you get far beyond the 20,000 mark in humans.

As you may be able to tell I could talk about this for days, but I've probably made your head spin enough for now. Feel free to get in touch via the contact section of the website if you have an questions.